FST BLOG

Intergenerational Justice and the Coronavirus Pandemic

- 15 June 2020

- General

- Patrick McHugh

The coronavirus is without a doubt the greatest challenge which the UK has faced since the War times, and it clearly demands a war-like response. Among the many parallels between our present predicament and wartime are the facts that more than a million mainly young NHS staff, plus thousands of medical students, are working around the clock to protect its capacity during the pandemic, just as the young heroes of the RAF defended our skies to give the country time to build up its military strength.

Some 12,000 retired doctors and nurses have returned to help on the front line in hospitals. The new Nightingale Hospital houses 4,000 patients in London, and a volunteer army of 500,000 has been recruited of all ages and backgrounds to help the NHS to ‘shield’ the 1.5 million most vulnerable people.

The intergenerational cooperation which we are seeing with the coronavirus pandemic offers a unique opportunity to reverse the trend of government providing more for older generations at the expense of the young.

We all, if we are lucky, grow old eventually; the challenge is to manage expectations and balance interests between generations, not set them against one another. A good society is one that values each and every life. Allowing the NHS to be overwhelmed by the coronavirus pandemic would risk the elderly dying undignified and lonely deaths in care homes, deserted in their hour of need. High quality health and social care services are not only beneficial to their mainly elderly recipients, but also support their family’s needs.

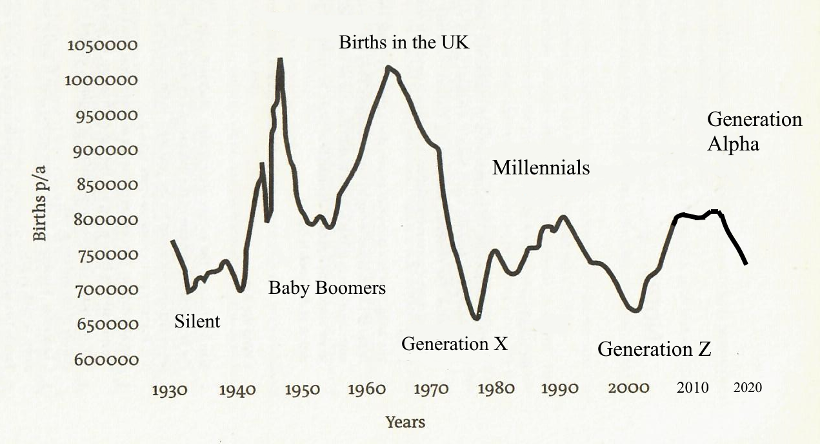

Fears about the future of our society and the strains in the economy from the coronavirus pandemic, increasing populations, biodiversity and global warming reflect a breakdown in the balance between the generations. The balance is mainly under threat from the baby boomers, born roughly between 1945 and 1965. Not because of deliberate selfishness but because of their sheer demographic and economic power. And younger generations are losing in the battle.

Image sourced from The Pinch: How the Baby Boomers took their children's future - and why they should give it back. David Willetts, Atlantic Books 2011, and updated 2020 by the author from ONS statisitcs, p. 271.

The relative size of the different generations has a big impact. The two peaks in births during the baby boom drove the twin social and economic revolutions of the 1960s and 1980s. Baby Boomers have also done disproportionally well; owning more than half of Britain’s £6tn of personal wealth; benefitted from house price booms; and are the beneficiaries of generous company pension schemes. It is now much harder for the younger generation to get started on the housing ladder or to build up a pension – the two main forms of personal wealth.

Despite the importance to future generations of the health care systems, economy, and climate change, the Baby Boomers are still getting preferential treatment. Despite cries from the young and the relative affluence of the Baby Boomers, the grey vote has fought tooth and nail against the BBC’s sensible termination of free TV licences for the over 75’s; deterred politicians from means-testing free travel passes; and resisted curbs on pension privileges. Many of the strongest deniers of climate change are those who will not be around to suffer its consequences. As Greta Thunberg said, ‘The eyes of future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say – we will never forgive you’.

Although historically future generations have generally been better off than the last, this is not the case for Gen X, Millennials, Gen Z and Gen Alpha.

If Baby Boomers, in effect, borrow from future generations, to deal with today’s problems in the economy, the global warming and pandemics then future generations’ prosperity will be blighted. And that is just what the Baby Boomers have been doing. They have been pinching too big a share of the wealth the nation is generating now and hopes to generate in the future.

Total physical investment in Britain is low compared with other countries. Even with massive infrastructure projects like HS2, Crossrail, the Thames Tideway sewer and 20% of our power coming from wind, we are not endowing future generations with the transport or energy infrastructure they need to be prosperous. Even when we do have physical assets, they do not necessarily belong to us, as we have to raise funds by selling our airports or nuclear power stations to foreign companies. Successive generations are not going to be able to enjoy the benefits of an income from these assets. The output we produce in Britain will not necessarily yield revenues for British people.

Economists attach importance to future generations through a discount rate, attaching value to nothing more than a generation ahead. The environmental movement though is forcing us to rethink about value in future generations. Rather than simple discount rates we need to consider further the burdens placed upon our grandchildren. There is a predictable and clear pinch point which appears to be most acute in 2030. The world no longer can be considered as having unlimited resources just waiting for our enterprise. It will be 2030 when demographic pressures are intense as the Baby Boomers age in the West and the youthful population surges in Africa. Demographic pressures, climate change, energy security, pressure on food, pandemics and water supplies all add up to a time of peril for humanity.

It is difficult to estimate the tsunami effect of the coronavirus pandemic, but the Government is probably taking a relatively moderate model to estimate the worst case. Even this is frightening as by the beginning of June, when the economy began to unlock, one million seven hundred thousand people may have had the virus, over 154,000 people have tested positive and over 39,000 who have been tested for Coronavirus have died.

World leaders have decided to prioritise the reduction of deaths from coronavirus among the old at the expense and livelihoods and prospects of those who are still at work. On that basis the world’s leaders are weighing the environment, the nation’s jobs, businesses and the whole of the younger generation’s and working population’s prospects against an imperative to keep the smaller and older part of the population alive. On that basis the older generations owe a vast debt to the young.

How can the Baby Boomers repay their debt to the millennials? The answer lies in the extraordinary response to Fukushima.

Atsufumi Yoshizawa, who was in charge of two reactors at the Fukushima facility does not look like a man who spent the best part of a year in the thick of battle. Yet that is how he describes his time among the group of engineers, technicians, soldiers and firefighters who risked their lives to remain at the heart of Japan’s worst nuclear crisis. The international media named them the Fukushima 50, although the number of workers who stayed to handle the triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant ran into the hundreds.

When Japan’s north east coast was shaken by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the afternoon of 11 March 2011, Yoshizawa was certain of two things: he would not flee, and he would not die. Less than an hour after the earthquake the plant was struck by a tsunami more than 3 metres high and far higher than the facility’s protective seawall had been built to withstand.

The scale of the disaster left the plant workers short of protective suits and the stocks of personal protection monitors had been damaged in the tsunami. It wasn’t until December 2011, when the government declared the damaged reactors had reached a stable condition known as cold shutdown that Yoshizawa and his colleagues were able to return to anything resembling regular working conditions.

While they slowly withdraw from Japan’s public consciousness, the Fukushima 50 say that they will never forget their time at the centre of a nuclear disaster that, without them, could have been so much worse. ‘There is a special bond between us’, says Yoshizawa, ‘I can’t put it into words – it’s just a feeling we have towards each other. I guess it’s the same camaraderie soldiers experience in wartime. In our case, the enemy was a nuclear power plant. And we fought it together’.

The extraordinary story of Atsufumi Yoshizawa gives a clue as to how the baby boomers can repay their debt to the millennials. Expert volunteers willing to take appropriate risks can supplement and support operational activities even in the face of huge natural disasters.

To reduce fears about the future of society and breakdown of balance between generations needs a coordinator and planner to bring together the Baby Boomer experts who have so much to offer to the other generations. A model for this is Engineers Without Borders which started when a group of engineers gave their time and their skills to help people in Ethiopia during the famine of the early 1980s. Now there are 60 organisations around the world. Engineers Without Borders UK emerged at the beginning of the millennium, during an era of greater global consciousness, which saw the world commit to the Millennium Development Goals.

The coordinator and planner should set up a process to bring the expertise of the Baby Boomers to assist organisations to resist strains in the economy from the coronavirus pandemic, increasing populations, biodiversity and global warming. The Managements Consultants livery company in the City is seeking to establish such a process under the title Securing Future Prosperity.

The Baby Boomers are likely to be financially sound - usually more asset rich than having significant income. They will also be experiencing poor returns on investments and liquid assets, want to contribute for various reasons including boredom and have lots to offer. Whilst pro bono work from the Baby Boomers is to be applauded a mixture of reward is also desirable. However, our tax environment has historically disincentivised this sort of engagement. We could lift restrictive prohibitions by for example removing Capped Pension Contributions, making EIS and SEIS applicable to Directors or Connected parties, creating a 0% investment income band, removing Dividend 0% income band restrictions, requiring on-going NI contributions when already fully entitled and extending further the pensionable age.

If these things ring bells with the recipients of this post, that's a strong indicator that there is an opportunity to push for changes that could be of great benefit to all concerned. All this taking place in an economy that has to be innovative.

A further task of the coordinator and planner will be to seek a declaration from Baby Boomers across the UK that they support this intergenerational cooperation. What we need to see is the Baby Boomers declaring that they will help organisations develop and implement new business processes as indivisible components of a larger, constantly regenerating and self-sustaining system in light of the coronavirus crisis.

If Baby Boomers value the future then they will cooperate with other generations for the simple reason that that will lead to them receiving reciprocal benefits in the future. It is hard to envisage the accumulation of social capital unless everyone values the future. The more we value the future the wider becomes the circle of cooperative reciprocal intergenerational arrangements that are possible for us. It can be done if we see what we do today as part of a story linking past, present, and future. That is what we can do in a family and in a nation and perhaps even globally.

Patrick McHugh BSc(Eng), BA(Hons), FIMechE, HSEE, CEng serves as an independent panel member for public appointments, on national committees, foundations and charities and on boards representing chartered engineers, environmentalists, management consultants, retail, education and technology. He has also been the Honorary Secretary for the Foundation for Science and Technology for the last 28 years.