FST JOURNAL

Hydrogen and Net Zero

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/CNLO5061

A crucial role in decarbonisation strategies

Baroness Brown of Cambridge

Baroness Brown of Cambridge DBE FREng FRS, Julia King, was Vice Chair of the Climate Change Committee for 12 years and continues to advise the UK Government as Chair of the Adaptation Committee of the CCC and as a member of the Hydrogen Advisory Council. She chairs The Carbon Trust and is a non-executive director of Ørsted and of the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult. She led the King Review on decarbonising transport (2007) for the Chancellor of the Exchequer and was the Sector Champion for the Offshore Wind Sector Deal, part of the UK Government’s Industrial Strategy.

The Climate Change Committee has developed a ‘Balanced Net Zero’ pathway out to 2050 as part of the analysis for the sixth carbon budget, including a description of the role that hydrogen can play in that journey. The main uses of hydrogen in 2050 are projected to be in shipping (as ammonia) as well as areas of manufacturing where decarbonisation cannot readily be achieved using electricity.

Hydrogen use is expected to grow from a small base today, to energy usage equivalent to our current electricity consumption – huge growth over a period of just 30 years. A doubling in the size of the electricity system itself will be needed by 2050, as transport is electrified together with much of our heating and some of our industrial processes. On top of the electrification of the core economy, a significant amount of electricity is likely to be used for hydrogen production.

Cost-competitive hydrogen

Today, renewables account for about 30% of grid-connected electricity. By 2050, with the cost of renewables coming down so fast, electricity generation could be around 80% renewables. The 120TWh of hydrogen production will therefore come from low-cost electricity, very low cost at times when hydrogen production is used to balance renewable generation because electricity demand is low – making green hydrogen cost-competitive.

By 2050, the Committee is projecting that about half the methane still used will be for direct power generation with carbon capture and storage (CCS), while the rest is used for blue hydrogen production. Hydrogen demand by that time will be predominantly for manufacturing and shipping with small amounts going into buildings, electricity generation and transport.

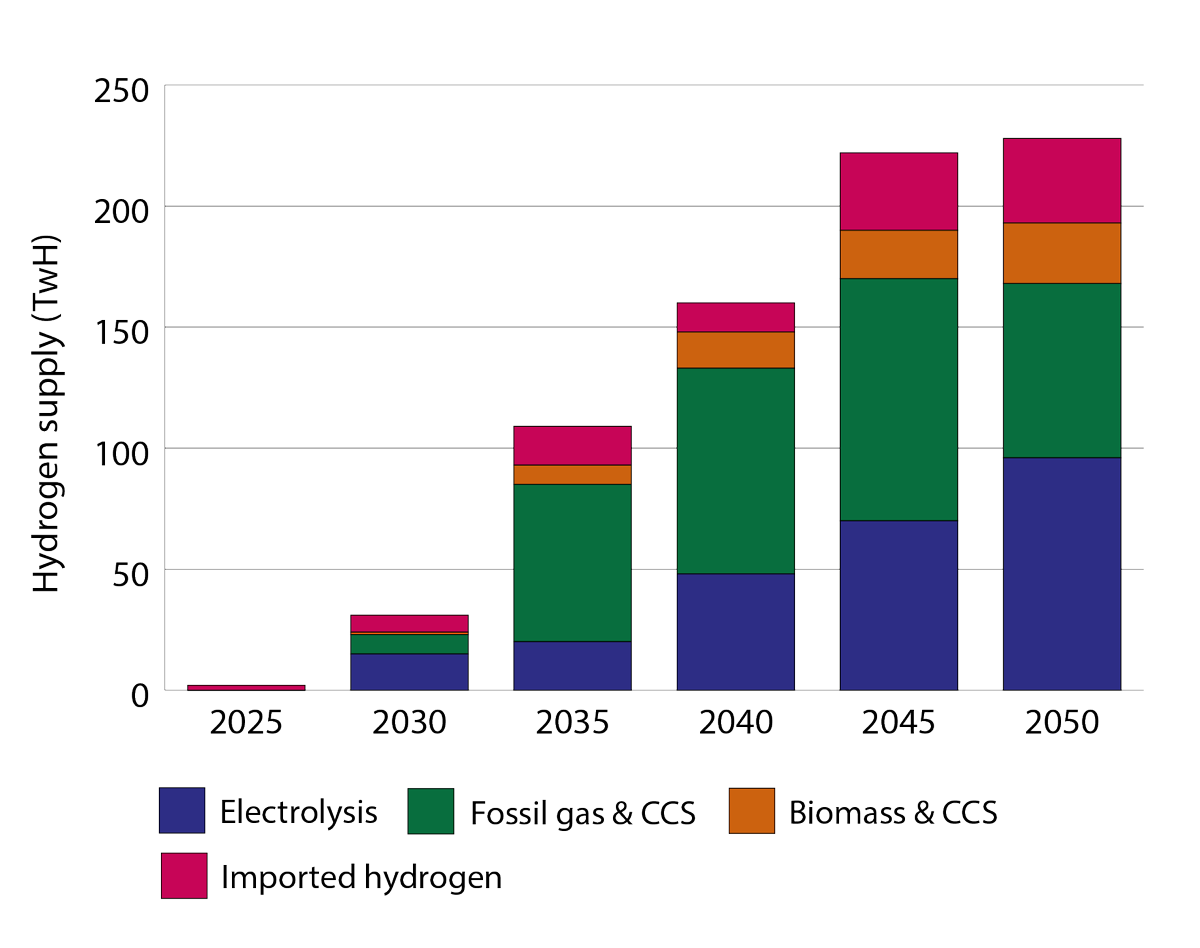

The majority of that hydrogen will come from electrolysis, as green hydrogen. It is likely that there will still be some fossil-produced hydrogen, with CCS - blue hydrogen. Further green hydrogen may come from biomass, and imports, but the UK could also be an exporter of hydrogen by 2050.

The UK is going to need significant amounts of hydrogen. It will be essential to decarbonise some key areas and hydrogen could support decarbonisation in quite a broad range of applications.

The opportunities for the UK are extensive. With an 80% renewable grid by 2050, there will potentially be a lot of very cheap electricity. The country also has extensive capacity for carbon storage around the coast.

There is already an impressive UK supply chain, with some key players like ITM Power and Johnson Matthey. Oil companies are looking to supply hydrogen as a major fuel. The UK is home to manufacturers of fuel cells, electrolysers and specialist storage tanks. This is a real opportunity for the UK to be the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) of the hydrogen industry, as well as potentially an exporter of hydrogen. The country has a world-class academic base in electrochemistry and materials, as well as other fields that underpin a hydrogen industry.

There are challenges, though, and the first is cost. Hydrogen is typically made from methane with CCS or electricity, so it will be more expensive than either. Therefore if you can use either directly, you will.

[Source: Climate Change Committee]

[Source: Climate Change Committee]

Hydrogen features strongly in new energy policy – a commitment to produce 5GW of low carbon hydrogen by 2030 has been raised to 42TWh – consistent with the Climate Change Committee pathway.

A challenging molecule

It is also a challenging molecule. It is very small. There have already been concerns about methane leakage from gas pipelines and hydrogen leakage is going to be more of a challenge. It can also embrittle high-strength steels and welds, so there will need to be careful testing of high-pressure systems. Energy density is an issue. In order to store and transport hydrogen, it must be compressed or, ideally, liquefied – a very energy-intensive process.

There has to be a systems approach to the use of hydrogen. It will be critical for production, transport, storage and use and all the other elements of the system to work together. The hydrogen system must also be integrated into the existing energy system. It is a complex systems integration challenge, not just an individual technology issue.

On top of the electrification of the core economy, a significant amount of electricity is likely to be used for hydrogen production.

Hydrogen features strongly in new energy policy. The Ten Point Plan last November committed to 40GW of offshore wind and 5GW of low carbon hydrogen production by 2030. The Energy White Paper in December turned the 5GW into 42TWh, which is consistent with the Climate Change Committee pathway. There is the Zero Carbon Hydrogen Fund and a Hydrogen Strategy is due this year. The work of the Government’s Hydrogen Advisory Council is feeding into that Strategy. Critically, next year we have the work on hydrogen business models – how to commercialise the opportunities, how early support mechanisms will work. There is a proposal to introduce a 20% blend of hydrogen in the gas grid by 2023.

Hydrogen will be a key part of meeting net zero, but it is not a ‘silver bullet’. It will be the energy source for applications that cannot be electrified, but it still has to be zero-carbon.