FST JOURNAL

Innovation Strategies

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/JAQO3170

Creating a leading innovation economy

Jim McDonald

Professor Sir Jim McDonald FREng has been Principal and Vice-Chancellor of Strathclyde University since 2009. He co-chairs, with the First Minister, the Scottish Government’s Energy Advisory Board. He is Chairman of the Independent Glasgow Economic Leadership Board and is a past-Chair of the Board of the Glasgow Science Centre. In October 2019 he was elected President of the Royal Academy of Engineering, becoming the first Scottish holder of the office.

In Scotland, we are building on a real position of strength. Aside from classical engineering as well as the health and life sciences capability, Scotland has a real innovation culture. It is worth mentioning, for example, that Glasgow has the largest small-satellite manufacturing capability outside California. There are around 160 companies in this cluster.

The M8 corridor is one of the world's leading photonics and quantum technologies centres with £2 billion annual turnover and 80% of production going to export. This sector’s total GVA is higher than the pharmaceuticals sector. Not that these are in competition, because the challenge is to navigate what is sometimes referred to as the ‘white space’ between sectors in order to tackle some of the cross-cutting issues like digital technology and net zero. We are in the process of developing a world class quantum corridor in the Central Belt, with computing breakthroughs occurring in the M2L innovation park.

The big question is how to capitalise on this? This conversation has been going on for as long as I have been involved in universities and working with partners in industry. How can we find the great technologies and ideas that will make a real difference? Clearly this involves supporting researchers, innovators, entrepreneurs and business. Reassuringly, the public sector has been developing this agenda really fast in response to industry expectations.

The most recent research excellence figures (REF2021) judged 85% of Scotland’s research to be world-leading or internationally excellent. Now that is an average and there are some universities that are doing even better but overall that is a very powerful cluster of top universities.

These universities are full of extraordinary talent. The funding mechanisms depend on the talent we have here. In Scotland, there are 80,000 postgraduates and 280,000 undergraduates, more than the population of Belfast or Nottingham: it is a city’s worth of research talent.

Commercialisation

In order to maximise that talent, we must improve and accelerate our performance in commercialisation. Nevertheless, analysis shows that in the past decade, between Glasgow, Edinburgh and Strathclyde universities, 137 spinouts have been created: as many as the northern research axis of Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds, and as much indeed as the Cambridge University Super Cluster over that period.

Innovation will always be hindered without absolute commitment to diversity and inclusion. Independent analysis has shown that over the past decade less than 3% of founders around the UK have come from an all-female team. Only about 11% of startup teams included females in them. There is real opportunity for improvement here.

Strathclyde’s Technology and Innovation Centre (TIC) is in the heart of Glasgow City Innovation District. This ecosystem is one of the exemplars referred to in the UK R&D Roadmap, where large companies, innovators, the SME supply chain and academia all come together.

All these players have been working together in response to the Levelling Up White Paper, in which £100 million were committed to create Innovation Accelerators in the UK: in Manchester, West Midlands and in Glasgow. Some £32 million of investment is being committed in Glasgow to get this process started, which will in turn leverage at least twice that over the next few years as capability builds across these innovation districts, working hand in glove with industry partners.

Of course, £100 million across the UK is not going to meet all the opportunities. It is just a starting point from which to leverage billions of pounds worth of investment. These Innovation Accelerators and Innovation District concepts are really important.

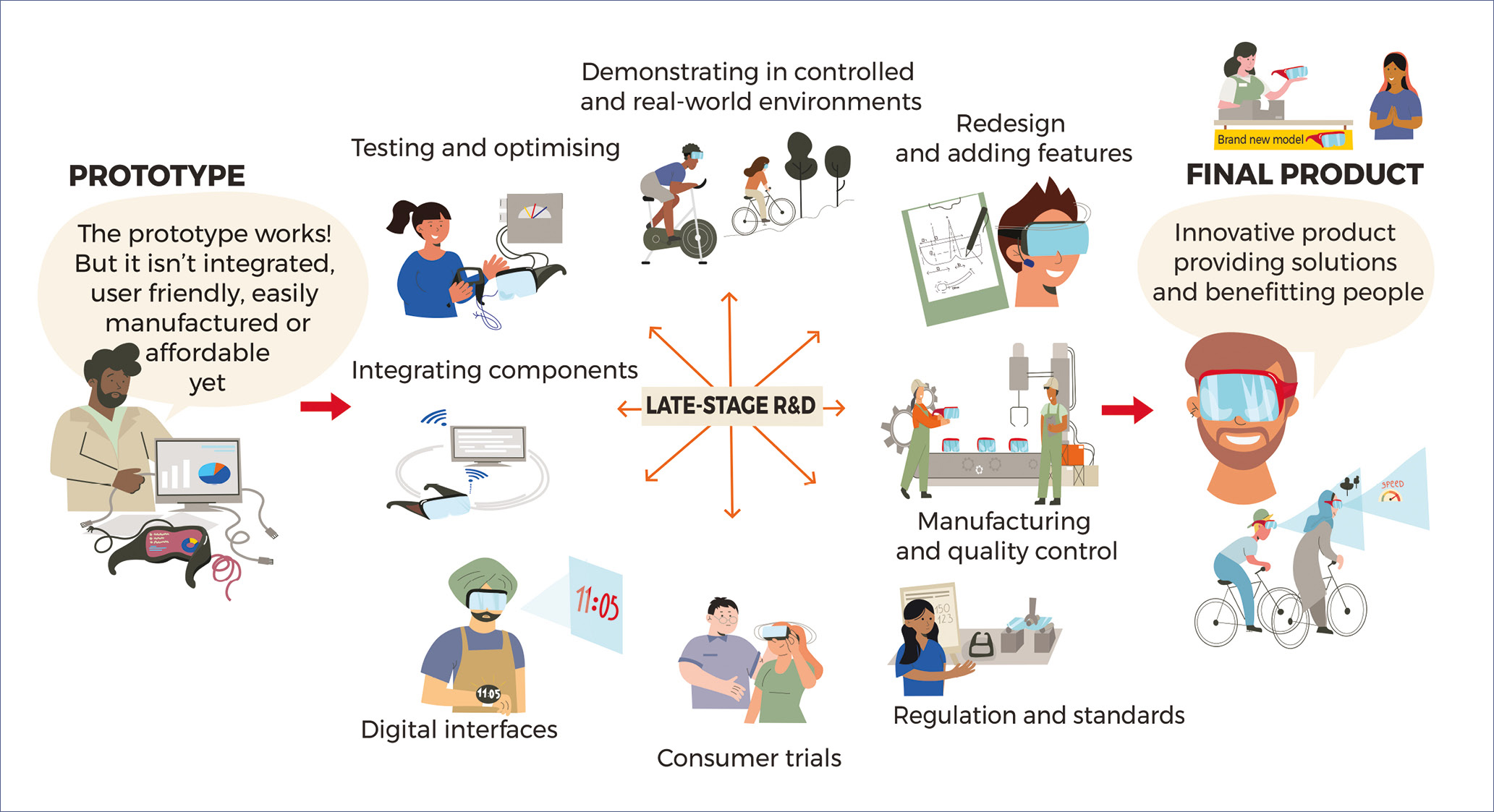

The Royal Academy of Engineering has been promoting late stage R&D, taking a proof of concept or prototype through to commercial application.

The Royal Academy of Engineering has been promoting late stage R&D, taking a proof of concept or prototype through to commercial application.In terms of measuring the impact of these initiatives over time, there has to be a commitment to weaving an innovation infrastructure that lasts right across multiple cycles of government and makes it a national capability going forward.

Through its emerging Innovation Strategy, Scotland can become one of the most innovative small nations. We are big enough to be effective, but small enough to be nimble and agile and so seize these opportunities. We have all the ingredients for success, with great research capabilities, good investment support infrastructure and late-stage R&D. The Royal Academy of Engineering has been promoting the journey from R&D to Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) 4-5 and beyond, validating research outputs through development at scale ready for market.

There is no magic single ingredient, rather a mix of ingredients which involves Government, academia and industry working together to identify what is important nationally. Individual clusters have different players, different supply chains, different technological risks and different market opportunities.

10-year horizon

This Strategy has a 10-year horizon and it sits alongside the current Scottish Technology Ecosystem Review, and the National Strategy for Economic Transformation. But there must not be a series of parallel streams, we need convergence initiatives and a sense of essential measures we all agree upon. That includes identifying the sectors we will focus upon, such as health and life sciences, energy, manufacturing, quantum and photonics. The existing evidence base will provide some assurance over what needs to be done.

It is important to be sure how innovation will be supported. There are a number of funding bodies: Scottish Enterprise, Scottish Funding Council as well as regional ones like Highlands & Islands and South of Scotland Enterprise. Now, we should not be starting again with a blank sheet of paper, but there should be high levels of expectation about their ability to lead on innovation. After all, this Strategy has to be delivered in just 10 years.

We need to identify now what actions have to be taken in the next couple of years to give us confidence in the ability to deliver. We cannot take investment for granted, either. Research England committed an extra £30 million last year for commercialisation efforts and have just announced a further £20 million. While we are not in competition with England, we do need to match up in terms of the level of expectation, commercialisation and entrepreneurial effort. Rather than just expecting to have this supplied by Scottish government, let us make an exciting investment proposition and the money will flow in.

So, the overall message is that Scotland is a really exciting place to be: great universities, great people and a growing level of exciting ambition. There is a real opportunity for this Innovation Strategy to make a difference now, over the next few years, indeed the next decade – and we can all play an important part in that.