FST JOURNAL

Viewpoint

There have been a number of attempts to identify the right technologies for the Government to support. That selection will change over time and according to national and international political circumstances.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/PKZH2940

Identifying the technologies that will be key to the UK’s future

David Willetts

The Rt Hon Lord Willetts FRS HonFREng was appointed Chair of the Foundation for Science and Technology in December 2018. He is the President of the Resolution Foundation. He served as the Member of Parliament for Havant (1992-2015), as Minister for Universities and Science (2010-2014) and previously worked at HM Treasury and the No 10 Policy Unit. Lord Willetts is Chair of the UK Space Agency, and a visiting Professor at King’s College, London. He serves on the Board of Darktrace, the Biotech Growth Trust and SynBioVen. He is an Honorary Fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford and a member of the Council of the University of Southampton.

There have been a number of attempts to identify the right technologies for the Government to support. That selection will change over time and according to national and international political circumstances.

Technology horizon-scanning is back in fashion – promoted by a renewed interest in its significance for national security and industrial capacity. We currently have five priority technologies. Before them there were seven technology families in the Innovation Strategy prepared after a very thorough consultation. My own contribution as Science Minister was the Eight Great Technologies which we launched in the Autumn of 2012.

I drew on technology horizon-scanning exercises by the Chief Scientific Adviser’s office and by Innovate UK, distilling them down into a simple list which I explained in a pamphlet for Policy Exchange. The narrative behind it went roughly as follows:

“The digital revolution is the big technological advance of this century and we will invest in key applications where Britain has distinctive strengths and there are global business opportunities such as: AI and big data; Space and satellite data; and Robotics and autonomous systems. Those are the first three technologies. The greatest scientific discovery of the past 75 years, genetic code, itself comes in a digital form. The future is the interaction of dry digital technologies and the wet biological world. Britain has invented every major genetic sequencing technology and has a good regulatory regime for applying engineering techniques to genetics. We will invest in new technologies made possible by these advances, notably: genomics and synthetic biology; regenerative medicine; and agri-science – our three wet technologies. Yet none of this will happen without also investing in two key foundational technologies – storing low carbon energy to drive it and the advanced materials without which the kit and the sensors won’t work.”

I followed up with a pamphlet describing the Eight Great Technologies more fully. Instead of vague talk about Industrial Strategy it was intended to test specific propositions: that Government could successfully identify key general-purpose technologies and that it could back them on their way to successful commercialisation. 8GT would be a test case to assess whether the sceptics who doubt the value of these exercises were right or not. So my speech launching the pamphlet in 2013 invited the audience to “imagine that today we are burying a time capsule and we are going to open it up in 10 years when we take stock.” So I have now published for Policy Exchange a review of how that exercise looks 10 years on.

By and large, identifying those eight has stood the test of time. Ten years on it is not a bad list. I hazarded some rather bold speculations such as “opportunities for the UK to host a space port if we get the regulatory framework right.” Quantum had not quite registered then and came along soon afterwards – some called it the ninth technology. I underestimated how long the application of technologies such as self-driving cars or new battery technologies would take. Cell and gene therapies have done well, though I got the balance wrong and focussed more on the cell than the gene which is where the real action has been. It is a good example of the need for a bit of flexibility as a technology develops.

General to particular

Moving from general purpose technologies to particular companies is very difficult. In the original pamphlet I picked out one synthetic biology company as an example – Green Biologics, which tries to use engineering of biology to modify an organism so it makes key chemicals. I did, though, warn that after development of such an organism: “The next stage is just as tricky – the steps between an organism in a lab and a full-scale industrial process.” Green Biologics closed down in 2019 and one report on its demise explained that the company never got to a full-scale industrial process. It is just one example of the difficulties of scaling-up, which is both a financial but also a technical challenge.

Since then here have been further attempts at identifying key technologies. The Government’s Innovation Strategy of 2021 listed seven key technology families:

- Advanced Materials and Manufacturing

- AI, Digital and Advanced Computing

- Bioinformatics and Genomics

- Engineering Biology

- Electronics, Photonics and Quantum

- Energy and Environment Technologies

- Robotics and Smart Machines

There are also now five key technologies which will be the focus of the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT):

- Quantum

- AI

- Engineering Biology

- Semiconductors

- Future Telecoms

The National Security and Investment Act 2021 lists 17 key sectors and technologies where “Subject to certain criteria, you are legally required to tell the Government about acquisitions of certain entities.” The list mixes together key technologies and sectors and indeed the responsibilities of entire Government Departments. It includes six of the original eight great technologies. It is a dramatic reversal of one of the tenets of Britain’s free market model – an open market in company ownership. It reveals the biggest change in science and technology policy over the past 10 years which is the return of security issues to centre stage.

While BEIS had been prevaricating about any attempt to back key technologies and had run down the technology expertise of Innovate UK, the defence and security agencies were getting more and more focussed on them, partly influenced by the American model. A Cambridge tech entrepreneur put it very clearly when he asked me a few years ago: “How is it that the security services are so clear about the significance of my technology that they don’t want me to have anything to do with Chinese investors but the Treasury and BEIS are so doubtful that anyone can possibly assess if this technology is of any value that they won’t put in any British public support?”

Security

The new more turbulent global scene has brought security considerations to the fore. Scepticism about Industrial Strategy collapsed under the growing influence of the security and defence experts who set up and staff the Government’s new Science and Technology Council. This is a really significant long-term shift of policy and it is a reminder that innovation is often driven by war and national security. The most important recent statement of industrial strategy is not from BEIS or DSIT. It is the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy published in 2021. It sets out a Strategic Framework with four objectives of which the first is:

“Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology: we will incorporate S&T as an integral element of our national security and international policy, fortifying the position of the UK as a global S&T and responsible cyber power.”

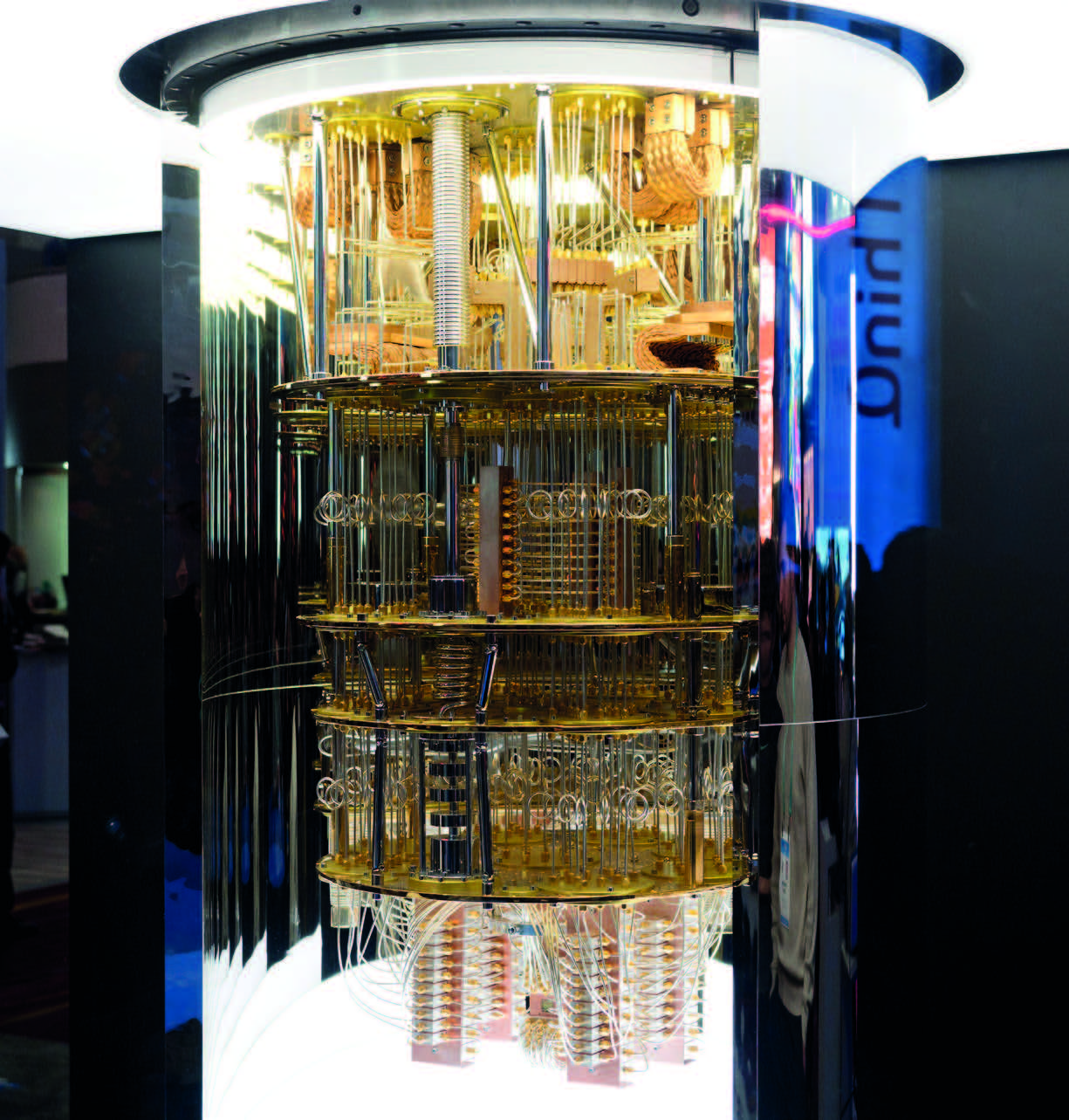

The IBM Q System One Quantum Computer. Quantum arrived after the original Eight Technologies had been listed – some called it the ninth technology.

The IBM Q System One Quantum Computer. Quantum arrived after the original Eight Technologies had been listed – some called it the ninth technology. Challenges

The key security focus is on general-purpose technologies, many of which are potentially dual-use. This is different from the civil focus on Challenges. That model lay behind Greg Clark’s Industrial Strategy of 2017 which had four challenges:

- Put the UK at the forefront of the artificial intelligence and data revolution

- Maximise the advantages for UK industry from the global shift to clean growth

- Become a world leader in shaping the future of mobility

- Harness the power of innovation to help meet the needs of an ageing society.

The Challenge is such a flexible concept that a technology like AI can be redefined as a challenge if that is where the funding is. But there are real challenges out there, of which the overwhelmingly most significant is the climate emergency. It makes sense to set that challenge and then harness a range of technologies to tackle it.

The application of technologies such as self-driving cars has taken longer than anticipated.

The application of technologies such as self-driving cars has taken longer than anticipated. I always enjoy discussing this issue with the charismatic Mariana Mazzucato who has made the case that Challenges should be part of the framework of innovation policy. They should be, yet they are not the whole story. Challenges can appeal to an anxiety regarding knowledge about real things by enabling policy to float above those key decisions. And they can be over-interpreted as meaning there is no need to invest in the underlying science and technology (which might give us the capacity to set future challenges). I co-chaired a Commission on the whole issue with Mariana and we agreed that there is a role for technology-push as well as Challenge-pull.

There is a role for Government too. New technologies and enterprises are on a long and tricky journey to the market. Easing some of the risks businesses face as they innovate is one of the best ways Government can promote growth. Government should not withdraw its support too soon and then expect commercial investors to take it on. It may hide its mistake by complaining that business leaders are risk averse but actually it is expecting them to take more risk than in many other countries.

This lesson is harder to learn because by the time there is an IPO and another unicorn floats on the Stock Exchange the original support from an Innovate UK programme may well have disappeared from view. Innovative companies usually only identify previous equity investments when they float. Non-dilutive funding such as Innovate UK grants are not part of the capital table so will not be visible, even to experienced investors coming in at that stage.

This promotes the illusion that all this ‘just happens’ because of savvy City investors with no public policy behind it. While bold, self-confident tech entrepreneurs and VC investors perform an invaluable role, they can understate the role of public agencies in getting these companies going in the first place.

Looking forward I am confident that there will be Government programmes to back key technologies. The issue now is the balance between backing them simply for their economic potential or whether the test today is whether there is a national requirement for them. We are still finding the right balance between the commercial and the security perspective. But without that security perspective, we would not have the attention and support which technologies now receive from Government.

- This article draws on the author’s paper for Policy Exchange, ‘The Eight Great Technologies 10 years On’