FST JOURNAL

A New Agency for Research and Invention

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/XGPV9670

A fast, flexible approach to addressing challenges

Dr Ruth McKernan

Dr Ruth McKernan FMedSci CBE has wide experience across business, Government and academic worlds. In business, she was Head of the Merck Neuroscience Research Centre, followed by Research Vice President positions in Pfizer in the US and the UK. She spent three years as CEO of InnovateUK, contributing to Government industrial policy, particularly through creation of the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund. As an academic, she holds a PhD in neuroscience with over 120 publications and 15 patents, mostly in the areas of ion channels and regenerative medicine.

We should think of the new agency as a public sector, new technology, venture fund. Its role is to deliver technology solutions for national security challenges, and the focus should be on speed and delivery. National security challenges can be interpreted quite broadly, including public health, energy or digital security challenges. As Chief Executive of Innovate UK, I led the development of the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund. During that process, we spent time talking to people from DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, in the USA.

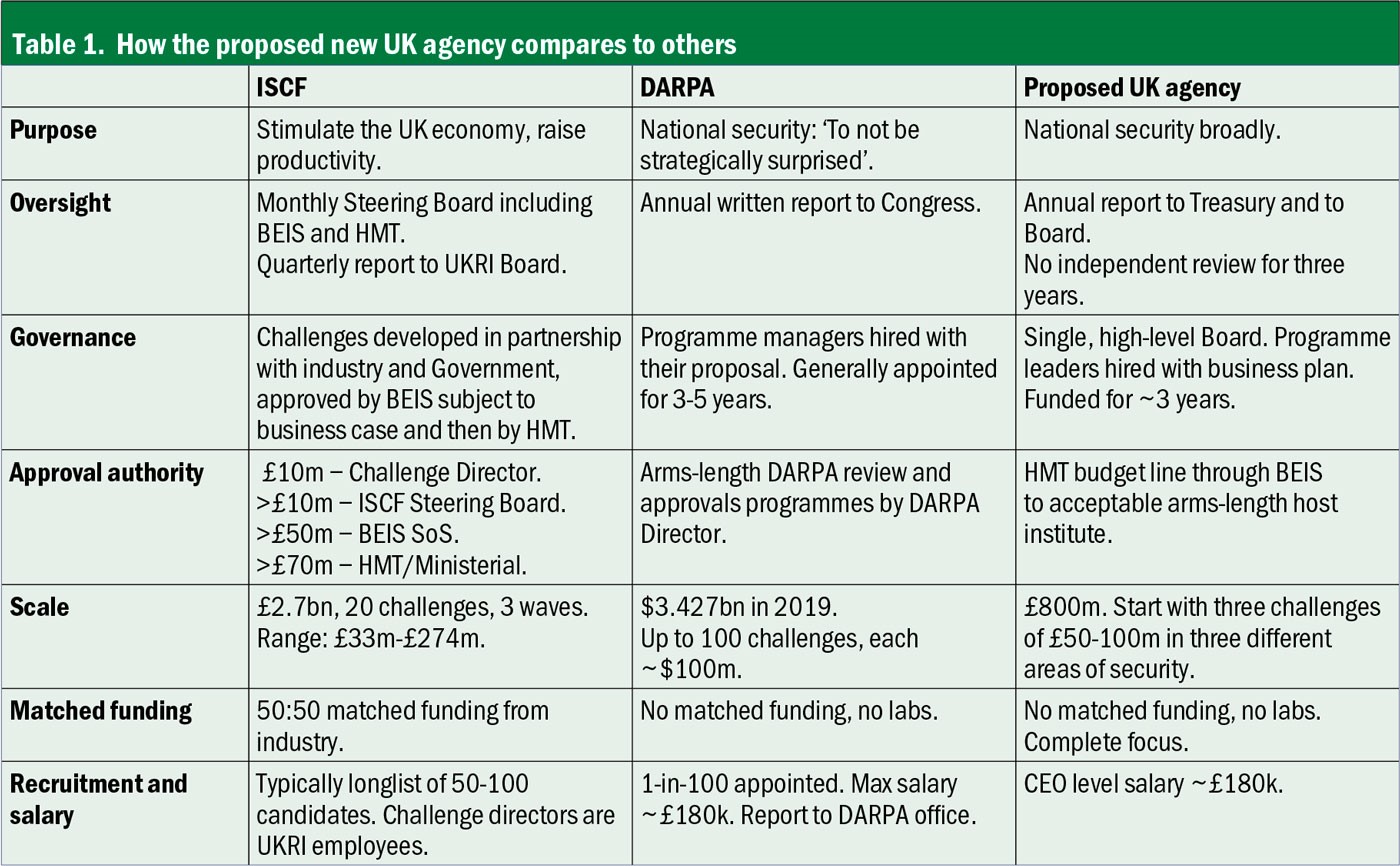

It is instructive to compare the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund (ISCF), DARPA and the place where I believe the new UK agency should sit (see Table). I believe that ARIA can be delivered by adopting elements from both DARPA and ISCF.

The purpose of DARPA and the new UK agency is national security, broadly. DARPA always said that their investment, or their funding, was to prevent the USA from being strategically surprised. The ISCF, however, was quite different: its goal was to stimulate the UK economy and raise productivity. ISCF’s focus was not about security, nor about having Government as a customer. It was to achieve business growth in areas of new technology and maintain the UK’s global competitiveness – but learning what did and did not work in the process is relevant here.

In the ISCF, there was a partnership with industry and Government from the very beginning. There was, after all, a considerable amount of public funds involved. There is some strong oversight: from UKRI, BEIS and Treasury as well as a number of levels of approvals. It has been a very rigorous and well-controlled programme: £2.7 billion, with currently 20 challenges. These range from £33 million – the Audience of the Future – up to £274 million for the Faraday Battery Challenge – and these awards require matched funding.

Oversight

DARPA operates differently: oversight is really light, just an annual report to Congress. The DARPA Director is appointed by Congress. It is really important that the new UK agency maintains as light an oversight as possible, so that leaders are able to work at speed and be very competitive.

For this new agency, the programme leaders should be hired together with their business plan, as happens with DARPA. They would be funded for three years in the first instance and really left to build their programme and deliver it, much as a Chief Executive would.

Programme leaders could be assigned to a host institute which need not sit within UKRI. So it could be the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), it could be a Catapult centre or a Royce institute, but being based in an arms-length institute would be a good place for them, and there are of course several hundred of these bodies in the UK.

It is important that the programmes do not need matched funding, nor their own labs; they would be virtual organisations, with the programme leader focussing totally on delivering the business plan as set out.

When it comes to recruitment and salary – this is difficult. It was not easy to find challenge leaders for the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund; we would consider 50 to 100 candidates before we found the right person and they are now UKRI employees with a salary in the range of £120,000. Yet, in my experience, the CEO of a biotech company with investments of £50 million would command an average salary more like £180,000 (which would not be out of line with DARPA).

Evaluating programmes

George Heilmeier, who was DARPA Director in the 70s, drafted a set of questions by which to evaluate proposed research programmes. These have become well-known as the Heilmeier Catechism and they cover: what you are doing, how it is done, what is the approach, who the customer is, what it will cost, how long will it take, what is the ultimate goal. They match well with the venture investment checklist of those things that should be in a business plan.

It is important to have a sense that this will work before money is assigned to a CEO and put to work. This new initiative should be, in essence, a venture fund. Obviously, it will not be there to make returns, but the feel of a venture fund, with the associated speed and flexibility, is a good way to look at it.

ARIA should need no additional legislation in order to get it up and running. The programme leaders should be entrepreneurial CEO-style leaders and the organisation should draw on people who have been serial entrepreneurs or who have been investors/venture partners in venture organisations. These would gather around them a small and predominantly industrial advisory group, because it is so important for them to have the advice they need in order to deliver. There would be a single, high-level oversight Board drawn widely from science, technology and Government. This Board might include, for example, the Chair of UKRI, the Chair of the Council of Science and Technology, the Government Chief Scientific Adviser, Ministers from BEIS and Treasury (or their delegates) and maybe one or two others.

The Board would select the challenge areas and the programme leaders (based on the individuals and the business plan) would then be selected by the Board. Innovate UK should run the processes and funding would be provided as a ring-fenced budget to a suitable host institution that the programme leader would choose themselves.

Managing the projects

The programme leaders would manage projects as they see fit. They could sponsor research in a university department, in a business, in a contract research organisation – it would be their choice. There are already mechanisms for follow-on funding through existing organisations such as Innovate UK or the British Business Bank. Ultimately, these individuals would be expected to deliver intellectual property, licensing and solutions to the challenges set out by Government. And then I would expect Government to be procuring those solutions as they are delivered.

So, to summarise: the new agency has to deliver technical solutions to national security challenges be they digital, health or defence, with a focus on speed – which means governance needs to be light-touch. It should be a virtual agency which takes advantage of existing infrastructure (no need for bricks and mortar) with programme leaders housed within existing institutes, operating more like CEOs of small flexible technology companies. ☐

It is really important that the new UK agency maintains as light an oversight as possible , so that leaders are able to work at speed and be very competitive.