FST JOURNAL

Advising Government

Science Advice in the UK

The UK has a well-developed framework for providing science advice to Government. A report published by the Foundation describes this system and how it might be adapted to other jurisdictions

At the end of 2020, the British Embassy in Santiago commissioned the Foundation for Science and Technology to produce a report looking at science advice in the UK. The idea behind the report was not just to explain how the UK system of science advice worked, but how this system has developed over time. This might prove of use to other countries as they develop their own science advisory systems.

The Chief Executive of the Foundation, Gavin Costigan, worked together with Anna Hopkins of Transforming Evidence, Dr Sarah Foxen of the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology and Dr Kathryn Oliver of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, to interview current and former Chief Scientific Advisers, civil servants, Research Councils, national academies, universities and others. This was in order to explore science advice from both the demand and supply side. The final report, Science Advice in the UK, was published in September 2021 and launched at an event in collaboration with the Chilean Science Ministry and the British Embassy in Santiago.

Government Chief Scientific Adviser

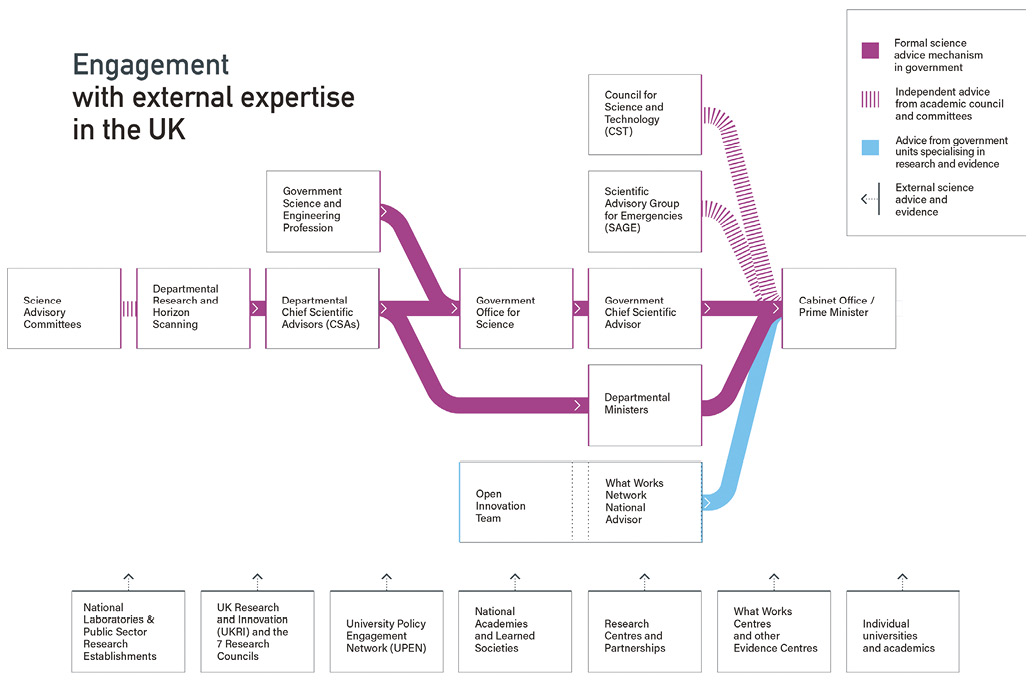

The report examines the role of the Government Chief Scientific Adviser (GCSA), and how that individual is sup- ported by the Government Office for Science. The role of the GCSA is a key feature of the UK’s Science Advisory system. The first GCSA was appointed in 1965 (although previous Governments had advisers of different kinds). In the UK system, the GCSA is not a political appointment, but a civil servant who is politically neutral and would stay in post if the Government changed. This person would typically be a leading scientist or researcher in their field.

The authority of the GCSA comes from the Prime Minister. Former GCSAs stressed the importance of having this authority, as it allowed them to work across Government and seek sup- port from officials and Ministers in different Departments. Trust is therefore a key part of making this work, as are some of the individual relationships involved.

It is clear that the individual holding this position cannot possibly have all the expertise needed, so a large part of making the role successful is accessing that expertise, either through existing structures or actively convening a group of experts when the need arises. Equally importantly, the GCSA has a role to communicate directly to the public about science and science advice.

This funnelling and focus through one person can be a real strength – in particular, it allows trust to build up between Ministers and senior policy makers, as well as the GCSA. However, it is also a potential weakness if those relationships do not work. Another potential weakness is a lack of diversity and inclusion if a very small number of people are involved in decision-making: systems are needed to avoid any “group think”.

Since the report was published, the National Science and Technology Council and the Office for Science and Technology Strategy (www.gov.uk/government/groups/office-for-science- and-technology-strategy) have been established to provide further avenues of science advice to Government.

The Government Office for Science

The GCSA is supported by the Government Office for Science (GO-Science). This is a central body within UK Government pulling together science advice. GO-Science has some specific commissioning roles (for example in Foresight and futures planning), and provides the secretariat for key committees, such as the Science Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE).

It is also helping the GCSA drive a cultural shift across Government to embed science advice in different Government Departments and agencies. In addition, it supports the Science and Engineering Profession across Government.

Government Departments

As in all countries, individual policy responsibilities are held in different Departments across Government and they have their own need for science advice. All Government Departments in the UK have a Departmental Chief Scientific Adviser (CSA) – but that was not always the case. Crises such as the Foot & Mouth outbreak of 2001 illustrated the need for a wider range of CSAs but it took several years for the network of CSAs to be fully established.

CSAs provide advice to their own Ministers and are line managed in their own Department, but a key feature of the system is that they network with each other and with the GCSA. Where needed, they feed in advice and expertise to the centre.

As with the GCSA, these are civil servants, not political appointments, and are usually established researchers. Often, they work part-time in Government and part-time in their university.

Like the GCSA role, the success or failure of the CSA role hinges around individual relationships, and the holders have greater authority and influence in some Departments than in others.

Some Departments also fund their own research and CSAs have a key role in shaping that science programme. There has been a recent exercise across all Departments to publish Areas of Research Interest: these identify to funders and researchers where the Department needs evidence. Again, different Departments have made greater or lesser use of their Areas of Research Interest and the process is still developing.

The UK has a well-developed framework for delivering scientific advice to Government

The UK has a well-developed framework for delivering scientific advice to Government

Committees

Many Government Departments access science advice via the use of expert committees. These have been established over time and there is no single model, although there are some central guidelines. There are also some central Government advisory committees, the best known of which is SAGE, the Science Advisory Group for Emergencies.

SAGE was originally established as a mechanism to gather experts in response to a crisis, typically of short duration. During the Covid pandemic, however, it has undergone a huge transformation. There has been a massive increase in its activities and the support given to it in order to provide the critical science advice needed by Government.

There have been inevitable issues of trust, mutual understanding and communication between Ministers, officials and advisers during Covid, but it is clear that it would have been much harder for the UK to tackle Covid if it did not already have existing science advisory structures.

Science and Parliament

As with Government, there are challenges in getting successful engagement between Parliamentarians and those with evidence such as academics. The Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology (POST) is Parliament’s in-house science advisory mechanism – it promotes links, produces briefing, holds events, delivers training on knowledge exchange and organises fellowships.

As with Government, structures and systems have evolved over time. Select Committees in Parliament scrutinise the work of Government and hold inquiries on relevant subjects; to do this they solicit scientific evidence and expertise.

There is, of course, a danger of always going to known experts. Parliament is aware of this and has taken active steps to broaden diversity of expertise – helped in part by providing incentives for academics to engage with them.

The role of funders

As well as the use of scientific evidence, there have been significant developments in recent years about how those with such evidence and expertise are improving the way they supply it. This has been partly driven by financial incentives, with UKRI and its Research Councils playing a bridging role between Government and the research community.

The biggest change in recent years is in the Research Excellence Framework (REF) which assesses research performance in the UK and awards Quality-Related (QR) funding as a result. In the past, this only measured the excellence of the research.

In 2021, 25% of the outcome was based on the excellence of the impact of the research – which includes policy impact. This provides a direct incentive for universities to engage with policy. There are other specific grant funds which have also been introduced, such as Impact Acceleration Accounts and the Higher Education Innovation Fund.

In some cases, Research Councils are working with Government to identify long term research needs and facilitating funding calls to address them. Some Councils also fund specific research and evidence centres, and they are building their own teams of evidence brokers.

The research community

There have always been academics who have worked with policymakers, but until recently this was very much down to the individual concerned. For many academics, there are many more incentives not to engage with policy than to do so, though the culture is slowly changing.

In recent years, driven in part by the financial incentives mentioned, universities have become more systematic in providing ‘evidence brokerage’, with specialist teams helping to bridge the gap between experts and policymakers. Such teams are involved in increasing both demand ‘pull’ and evidence ‘push’, as well as helping build skills in the research community and supporting secondments of researchers in Government an Parliament. The Universities Policy Engagement Network (UPEN), set up in 2018, aims to provide a ‘one-stop shop’ for policy officials.

The Universities Policy Engagement Network aims to provide a ‘one-stop shop’ for policy officials.

National Academies also play a crucial role, in particular because of their power to convene expertise. The major academies all have policy units, working both proactively and reactively in policy engagement. National Laboratories also provide evidence to Government, and a recent addition to the UK system has been the What Works Centres, which aim to increase the supply of tailored, policy-relevant evidence in specific areas.

Science Advice in the UK was published on 21 September 2021 by the Foundation for Science and Technology and Trans- forming Evidence. Transforming Evidence is a multidisciplinary, cross-sectoral, international community that aims to connect individuals and organisations who generate, share and use evidence. The report is available on the Foundation’s website (in both English and Spanish) at: www.foundation.org.uk/Document- Library/Science-Advice-in-the-UK (DOI: 10.53289/GUTW3567)